Lessons from public health history

Blattman’s Why We Fight is one of the most informative books I’ve read in years. I appreciate when social scientists engage in high quality science communication for the public. They have so much to offer, and it helps fill a void in an information environment with more trustworthy content.

A brief summary is provided below. I’m not going to go too much into critiques - many of which are valid. Instead, this post will cover something that was thought-provoking to me. In his recommendations for those who are interested in peace work, Blattman emphasizes that we should not confuse easy problems - which have clear solutions and a playbook for implementation - and wicked problems like war.

So the question I want to explore is how wicked problems transform into easy problems.

Brief summary of the book

The book begins by emphasizing that most conflicts are resolved peacefully, and very few actually descend into war. The argument is that we’re less likely to observe successful conflict resolution (or bargaining in IR speak). A similar observation bias may exist in many settings, ranging from national security to public health.

With that said, the book’s focus is to explain reasons for war, defined here as prolonged violence between two groups, and paths to peace.

The five mechanisms for wars are presented as:

- Unchecked interests and power - a leader or group with personal incentives for war, combined with lack of checks and balances and isolation from negative consequences

- Uncertainty - about the strength or resolve of an opponent and challenges with information-sharing

- Commitment problems - such as pre-emptive war and preventive war, motivated to avoid an undesirable outcome in the future; at least one side has concerns about another’s future behavior. This is presented as an unresolved bargaining failure that leads to war, or as a hinderace to resolving wars, especially civil wars.

- Intangible incentives - status, grievances, etc.

- Misperceptions - distorted views about probability of winning and other factors

Why these categories? Because that’s how they’ve been presented in the literature. The book draws from rationalist IR/conflict studies but also adds multidisciplinary perpectives from fields like psychology.

The four paths to peace are presented as:

- Interdependence - economic interdependence increases the opportunity costs of war. Social interconnectedness, as opposed to isolation or segregation, is pacifying because it promotes empathy while reducing “othering”.

- Checks and balances- constraint on unchecked power and private incentives

- Rules and enforcement - constraint on violence (though more downstream than #2)

- Interventions: punishing violence, enforcing peace agreements until they are self-sustaining, facilitating, information sharing to promote efficient bargaining, socializing or cultivating societal norms that frown upon violence and promote peace.

There are some really interesting examples of success. In the US, one such example is Chicago-based Becoming a Man (BAM) program which provides cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for young men. Another is Liberia-based STYL, a multi-pronged program that combines CBT with economic opportunites.

How do wicked problems become easy problems? Lessons from public health history

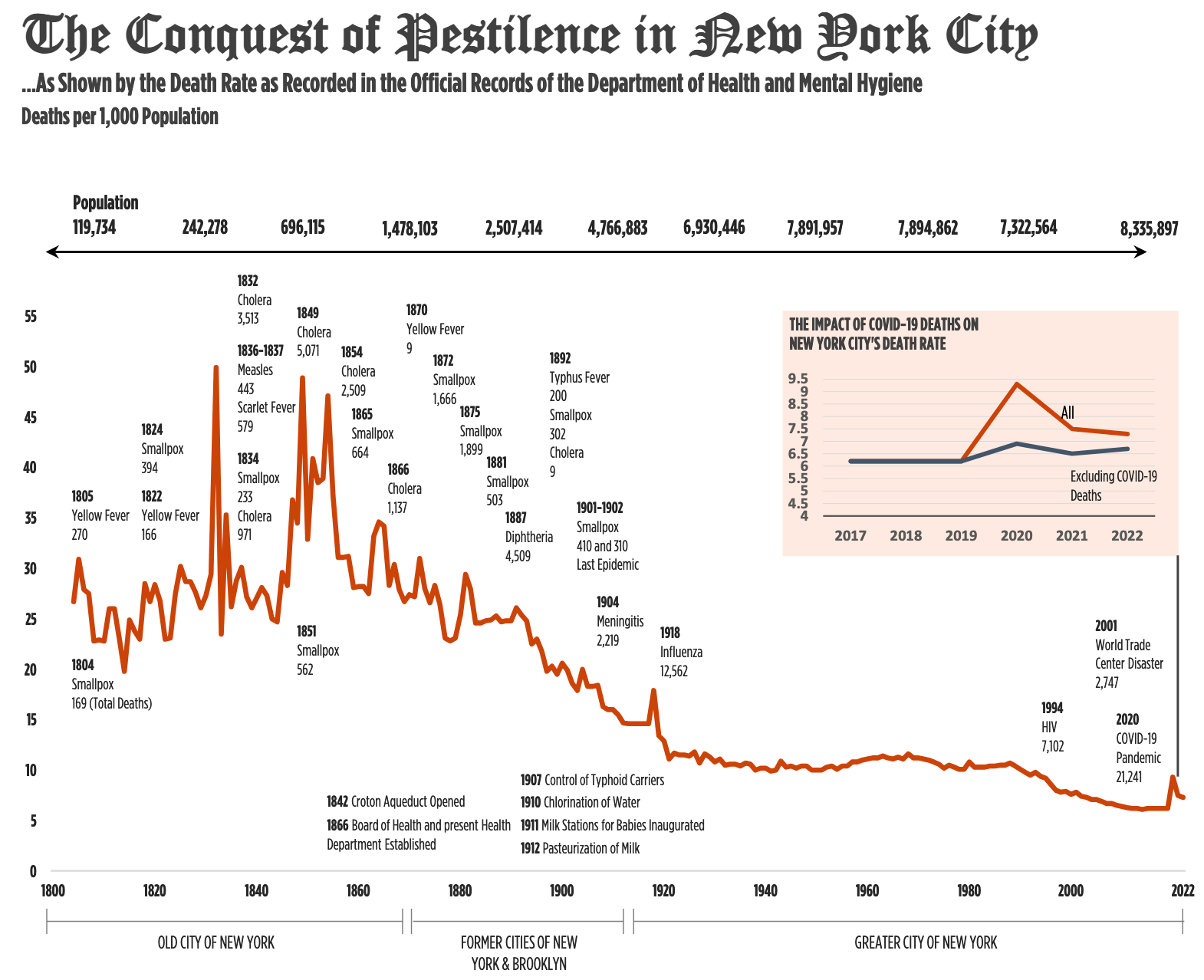

The book cites New York City’s successful campaign1 in 1947 to vaccinate millions against smallpox following an outbreak as an example of an easy problem. This doesn’t mean it was low effort. Instead, it means that there was a clear solution and an implementation playbook: vaccine technology existed, it needed to be scaled, and a massive population-level campaign had to be undertaken in a short time period. Yes, the reality may have been more complicated, but the larger point stands.

Given that epidemics were a wicked problem that ravaged populations for much of human history, how did we get to the point where they - or at least some of them - transformed into “easy” problems?2

First, a very abbreviated history of public health relevant to the New York City case study:3

- 1796: Jenner tests a smallpox vaccine, improving on the practice of variolation practiced for centuries

- 1803: First global mass vaccination campaign against smallpox begins (gnarly history that involves orphaned children)

- 1861: Pasteur publishes on germ theory of disease; development of more vaccines

- 1866: Metropolitan Board of Health comprised of experts is established to oversee more centralized infectious disease control and prevention for New York, Brooklyn, and Westchester County. Broad authority is granted by the state to address fragmented and often corrupt nature of existing apparatus.

The enactment of the Metropolitan Health Bill of 1866 was a major turning point in the history of public health not only in New York City, but in the United States as a whole.4

- In the subsequent decades, infrastructure is developed for epidemiological surveillance, investigation, control, response, and prevention

- Late 1800s-early 1900s: Epidemiological transition5 - reduced infant mortality and shifts in leading causes of death towards chronic diseases largely thanks to public health interventions (e.g. clean water, sanitation, reducing overcrowded housing, vaccine campaigns and mandates for children attending public schools).

- 1940s WWII and post-war, US government developed impressive procurement and scaling abilities; trust in government is fairly high

Some lessons from public health on transforming wicked problems into easy problems:

- Outbreaks, like war, are hard to predict in advance, but there is often a window of time during which they can be contained.

- Necessary conditions included:

- Science and technology: When the smallpox vaccine was first discovered, the mechanism of action was yet to be fully elucidated. It didn’t stop it from being useful. However, understanding the causes, mechanisms, and safety may make it easier to build a strong case and have buy-in, both for public trust and in solving coordination problems.

- Procedures for outbreak detection, investigation, and response. Public health is full of blueprints (CDC’s Field Manual wasn’t published until 1990s, but APHA’s Control of Communicable Diseases has been produced since 1917. Blattman warns against blueprints as a one-size-fits-all approach, and that’s sensible. But in public health they’re developed for different circumstances like mode of transmission. Later guidance incorporated cultural understanding and recognition of context.

- Authority and independence of the health department to lead the response - including implementation of the procedures, even though it lacked the power to mandate universal vaccination

- State capacity: health department, other city services, and federal government support (including the US Public Health Service and the military for rapid vaccine procurement)

- Sufficient conditions: Several key things made a difference in 1947:

- Decisive action by the commissioner of health to launch a mass vaccination campaign

- Solving coordination problems in a timely way - the health department led the coordination of city agencies, health care systems, and the federal government

- Strong risk communication strategy plus pre-existing public trust in government succeeded in persuading the public to get vaccinated.

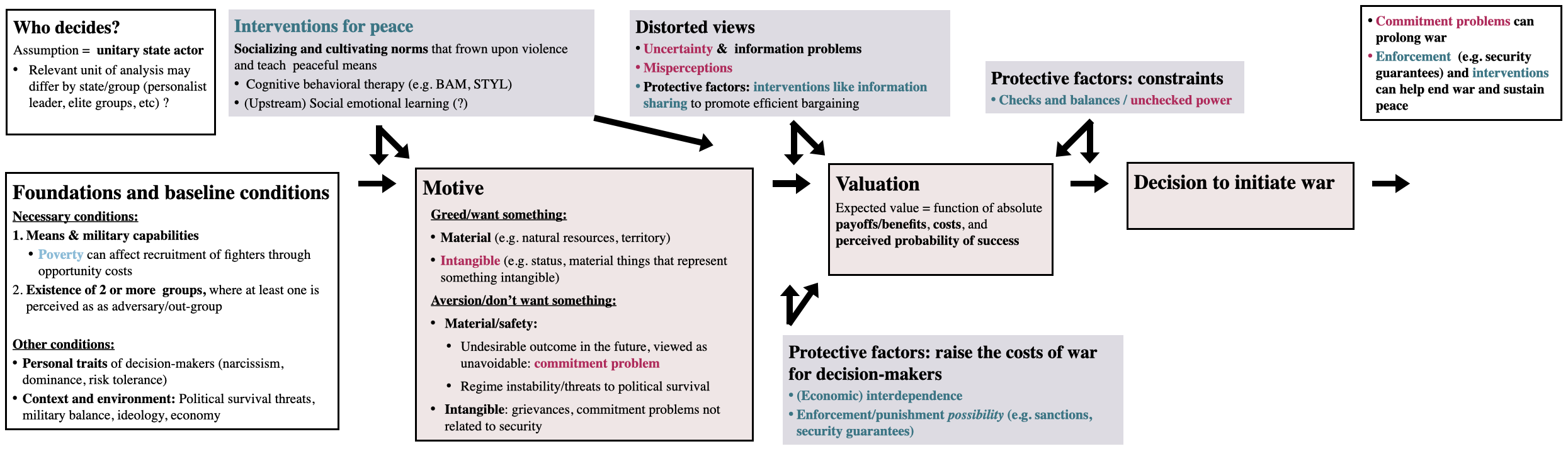

(Attempt) at a causal diagram of war initiation & what it suggests for prevention

Back to war. One of the things I struggled to understand was where the 5 causes/mechanisms fall in the causal chain. The diagram below is my best guess based on the book, plus some things I added. I’m not confident I got everything right (ChatGPT disagrees with me about commitment problems, and I kind of get it).

Notes: this is based on an extremely simplified motivation framework from psychology. Not meant to be a directed acyclical graph (DAG)! Arrow-on-arrow illustrates an effect modifier, per Figure 2 of Weinberg

(i.e. vaccine is an effect modifer, in that it only has an effect on an outcome like severe disease when there’s virus exposure).

Notes: this is based on an extremely simplified motivation framework from psychology. Not meant to be a directed acyclical graph (DAG)! Arrow-on-arrow illustrates an effect modifier, per Figure 2 of Weinberg

(i.e. vaccine is an effect modifer, in that it only has an effect on an outcome like severe disease when there’s virus exposure).

Necessary conditions for prevention:

- Science: The diagram suggests multiple intervention points to prevent war by addressing the 5 mechanisms - and that’s already actionable. However, the five causes aren’t a unifying framework: they represent the bargaining model (our closest thing to one) plus psychological factors not yet fully integrated.6 Also, most of the protective factors (checks and balances, enforcement, interdependence) appear to be downstream of motive and the multi-level factors shape it. There are opportunities for theoretical development. Progress in science is sometimes catalyzed by interdisciplinary approaches. For example, see Bandy Lee’s textbook for a bio-psycho-socio-environmental model of violence.

- Procedures for early detection -> response: Needs more development. Although the book critiques some approaches as misguided, it also highlights growing empirical evidence for what works.

- Global response authority empowered to lead the implementation of above procedures: anarchy problem means we don’t have global government. The UN was formed after WWII as a successor to the League of Nations with peacekeeping and enforcement power, but among its limitations is veto power by any of the 5 permanent Security Council members. Will it take another global conflict to improve it? Meanwhile, alliances like NATO, African Union / ECOWAS attempt some of this at a regional level but aren’t there (diagnosis, capacity, response).

- Capacity - ?

Other protective elements:

- Checks and balances: This constraint may be analogous to mass vaccination in public health - highly effective, but hinges on robust institutions and political will. As recent descent into authoritarianism in Hungary, Turkey, and the US shows, democratic institutions are vulnerable to hostile takeovers. This is a real issue, especially if this is done by individuals with personal traits like narcissism, risk tolerance, and drive for dominance - linked to violence and war.

- Interdependence - the world economy is pretty interconnected, with very few regime exceptions. This makes war costly, but only if the initiators internalize those costs. I’m less familiar with social connectedness measures. However, political polarization has been growing in the US for decades (trends in other parts of the world are mixed).

- One of the most effective upstream preventive factors discussed in the book is cognitive behavioral therapy for men. This is worth a lot of reflection. What the barriers to scaling what seem like life-changing programs?

- Social-emotional learning (SEL) is not in the book, but I raised it as a possibility in the diagram since it teaches emotional regulation and conflict resolution early in educational settings.

- Risk communication and information sharing - ?

Sufficient conditions for prevention:

- Solving coordination problems and timely, decisive action - epic fail, or also an observational bias problem?

Takeaways: research and policy priorities

Almost every condition for war prevention seems insufficiently developed. This means there’s need everywhere. However, some priorities stand out:

- The most successful, evidence-based upstream interventions for peace target our minds, and how we relate to others.

- Checks and balances are highly effective, yet are vulnerable to being undermined by those who are more likely to engage in violence. This presents opportunities for upgrading or designing new generation of institutions and their interactions.

- Coordination problems (and collective action?) - may be worth multiple Nobels?

The success of the above rests on a foundation that includes security and state capacity, underscoring both the hierarchy of needs and the feedback loops that can either reinforce peace or entrench cycles of violence.

-

Two great articles to learn more: Weinstein 1947 and Sepkowitz 2004. ↩

-

For a small glimpse into coordination problems and shifts in local authority during COVID-19 plus comparison to 1947, see: https://www.cityandstateny.com/policy/2021/01/why-cant-nyc-vaccinate-like-its-1947/175308/ ↩

-

For a less abbreviated history, here’s 700 pages by John Duffy. ↩

-

AJPH, 1966: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.56.5.699 ↩

-

Image source: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/vs/2022sum.pdf ↩

-

It’s possible that the psychological factors are part of the expected benefits/payoffs of war calculation. But the expected benefits are often treated as a given and receive less attention. ↩